Has modern digital technology made the development of virtue more difficult? As I have written elsewhere, I am not interested in arguing that virtuous living is more difficult today than at other times in history. Virtuous living has always been a hard, narrow road, and it always will be.

However, I also believe each age comes with its own unique blend of temptations and challenges to the development of virtue. One must understand the specific barriers to virtue development of their cultural moment and come up with a strategy for overcoming those barriers as they seek to live virtuous lives.

Cal Newport’s book Digital Minimalism presents some insights into the challenges we are facing today and how to overcome them. Let’s dig into it.

Book Details

Digital Minimalism: Choosing a Focused Life in a Noisy World

by Cal Newport

Author’s Blog

Other Works: Deep Work; So Good They Can’t Ignore You; How to Become a Straight-A Student; How to Be a High School Superstar; How to Win at College

Date: 2019

Pages: 254 (284 including notes and index)

Foundations

Part 1 of Digital Minimalism is a problem-solution proposition. Newport outlines what he sees as the dangers of modern digital technologies and then gives his proposed solution: of course, digital minimalism.

The Attention Economy

First, the problem. According to Newport, the real issue with digital technology is the business model, which he labels the attention economy. Multiple tech companies make hundreds of billions of dollars offering free services. Think Facebook, Google (the search engine and YouTube), Twitter, Instagram, Snapchat, etc. How do they make money? They sell advertisements. The business model looks something like this:

Number of users x Average time spent on the service = Revenue

The implication is subtle but incredibly important. It didn’t really sink in for me until I heard it stated this way: “If you are not the customer, you are the product.”

Facebook doesn’t make a social media site and sell it to individuals who want to be more connected to their friends and families. Facebook builds a mass of Monetizeable Daily Active Users and sells their time and attention to advertisers. They just happen to use a social media site that claims to connect people to their friends and family as a tool to gather the necessary eyeballs. Thus, the attention economy business model could be even further simplified.

Your Eyeballs x Your Time = Their Money

So, what’s the problem with that? Users get a free service, advertisers sell stuff, and Facebook makes money. Everyone wins, right? In theory, but as every good student of virtue is aware, greed messes everything up. Look back at the attention economy business model above. How can Facebook increase their revenue? Two ways: increase the number of eyeballs or increase the amount of time each set of eyeballs is engaged.

Time vs. Benefit

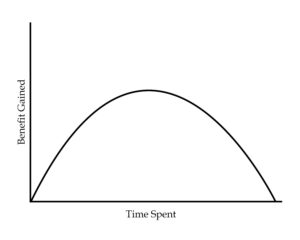

Attention economy companies do everything they can to increase the amount of time each user engages their service. Unfortunately, each of these services only offers a certain amount of real value and utility to their users, meaning at some point users stop benefiting from spending more time on the service. On a chart it looks something like this:

Based on this chart, logically, users will want to use the service up to the point of maximum benefit gained and not a minute more, bringing us to the peak of the curve. The reality is that we can get to the top of that curve much more quickly than we think, meaning the rest of our time is wasted. Whether we realize it or not, our time is our most valuable resource. Every minute we spend on one activity is a minute we can no longer spend on any other activity. If you are not convinced that your time is worth anything, take a minute to remember that companies are willing to spend real money for your time. However, unlike at a job where the company pays you for your time, in the attention economy companies (think those pesky sidebar advertisements) pay other companies for your time.

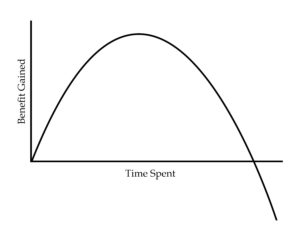

Therefore, many digital technology companies are fighting to control more and more of your time and attention so that they can profit from being the ones who can sell it to the highest bidder. Services like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter are something akin to a Trojan horse. They offer users a service purported to benefit the user, while engineering that service to control as much of the user’s time and attention as possible for the purpose of selling it. These companies want to push each user as far down the curve as possible to maximize revenue, regardless of whether it is actually good for you. Unfortunately, many users are finding that digital media’s dominance over their time can have very negative effects on things like productivity and sense of well-being. Therefore, our curve should probably look more like this:

Attention Engineering

It is in reference to digital media’s “attention engineering” that Newport makes his biggest contribution. He highlights how stacked the cards are against the individual user by pointing out some common flaws in human character and psychology and revealing the methods used by attention economy companies to exploit them.

Teams of attention engineers spend considerable resources making their services as addictive as possible. Nearly every new feature is presented as benefiting the user, yet the success of every feature is determined by whether it increases user engagement, aka increases “monetizeable attention.” The work of these attention engineers is made much easier due to the reality that temperance (moderation), self-control, and self-denial are rare virtues in our day to the point of near total neglect. Newport’s insights into the specific ways companies take advantage of both positive and negative aspects of our character is one of the chief benefits of the book, making it worth reading for that information alone.

Is Digital Minimalism the Answer?

Fully examining the philosophical roots of digital minimalism and evaluating it as a worldview is a bit beyond what I am prepared to do at this time. With that said, there are two parts of Newport’s solution I consider truly valuable steps toward a better relationship with digital technologies.

Eat the fish, spit out the bones

The goal of Newport’s digital minimalism is to use digital technologies in a way that supports your values and no more. This is far different from a full embrace or complete rejection of these technologies. Newport argues it is possible to win the battle over the attention curve and derive maximum benefit without getting sucked further down the curve, but that it takes much more work and intentionality than most of us are inclined to commit.

I like this solution, which is neither alarmist nor complacent. Digital minimalism shifts the conversation from what a technology can do to how a technology can be used to support or disrupt our existing goals and values. One complicating factor is that many technologies have unintended consequences and subtle effects on our hearts, minds, and souls that are difficult to predict and evaluate. The best case scenario for learning to handle digital technologies is a culture of collective wisdom and sharing of insights among a community with common values.

Avoid the Void

In a world where Netflix, YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, a 24-hour news cycle, ESPN, and a stream of text messages and snapchats can dominate many hours of attention per day for the average user, imagine the attention void it would create to stop all of these practices cold.

About a year ago, my wife and I decided to limit our television (including streaming) consumption to the weekends. We allow ourselves to watch something together on Friday and Saturday nights and have NFL in the background on Sunday afternoons. The rest of the week is off limits. We’ve found that our friends who know of our decision respond with shock and the bewildered question, “What in the world do you do on weeknights!?” The answer is complicated. We have more conversations, do more puzzles, and play more board games than we otherwise would have. However, honestly, we’ve also been bored sometimes. Our bedtimes have even gotten a little earlier on average.

Newport’s advice is to avoid the void created by reducing use of digital technologies by adding high quality offline activities to our lives. Obviously, these activities should be chosen and evaluated against our values and goals, but the point is that the more high-quality and rewarding activities we are involved in, the less susceptible we are to the low-quality, but highly addictive, activities targeted at us by attention engineers.

Suggested Practices

Part 2 of Digital Minimalism (actually the majority of the book) is devoted to laying out some practices for filling our lives with high-value replacements for undue time spent on digital technologies. As you would expect, this section, which is full of examples and suggestions, contains a lot of take-it-or-leave-it advice. I suspect that different suggestions would stand out as useful to any given individual. For that reason, the section is worth mining for helpful nuggets. I’ll briefly outline a few I found helpful.

Solitude

Newport adopts a definition of solitude from a book called Lead Yourself First, which defines it as “a subjective state in which your mind is free from input from other minds.” That is a worthwhile definition, though I would exempt the mind of God from that definition. I consider meditating on the mind of God one of the chief goals and benefits of solitude.

Regardless, there are a couple helpful parts of thinking about solitude as a high-value replacement for use of digital technologies. First, valuing solitude reminds us that not all boredom is bad. People tend to be bored when they are not being fed pre-packaged entertainment. I would suggest the modern definition of boredom is the same as our working definition of solitude: “A subjective state in which your mind is free from input from other minds.” To replace this harmful notion of boredom, it may be helpful to think of boredom as the combination of freedom from input from other people’s minds and the absence of output from our own minds. Thus, to reduce boredom, we can either seek input from others or use our own minds and hands to create something worth our time.

High Quality Leisure

This leads to Newport’s section on reclaiming leisure. He argues for the value of strenuous and challenging hobbies and leisure activities. Rather than going through all his reasoning on the subject, I will simply quote a section he writes about a famous president:

Theodore Roosevelt famously said: “I wish to preach, not the doctrine of ignoble ease, but the doctrine of the strenuous life. Roosevelt practiced what he preached. As president, Roosevelt regularly boxed (until a hard blow detached his left retina), practiced jujitsu, skinny-dipped in the Potomac, and read at the rate of one book per day. He was not one to sit back and relax.

And here is another representative section on the topic, here referencing a 19th-century work on the subject by Arnold Bennett:

In this book, Bennett notes that the average London middle-class white-collar worker putting in an eight-hour day is left with sixteen additional hours during which he is as free as any gentleman to pursue virtuous activity. Bennett argues that the waking half of these hours could be dedicated to enriching and demanding leisure, but were instead too often was acted by frivolous time-killing pastimes…After an evening of this mindless boredom busting (the Victorian equivalent of idling on your iPad), he notes, you fall exhausted into bed, with all the hours you were granted “gone like magic, unaccountably gone.”

It is counterintuitive to think that vigorous and strenuous activity in our leisure time will lead to more energy and passion in our work time, but I have found it to be true in a small sample size of my own attempts.

Conversation

One of Newport’s favorite ways to replace interaction with digital technologies is with genuine, face-to-face conversation. He says that social media and texting provide low-quality connections, sort of like touching base, but are poor tools for meaningful conversation. Interestingly, he actually encourages using technology, such as FaceTime and Skype, to enable conversations he considers further up the quality communication scale.

Still, there is no true substitute for face-to-face conversation. There is a reason we still visit our family at Christmas rather than simply ship presents to each other and open them over FaceTime. Newport argues that more meaningful conversations and face-to-face time with family, friends, neighbors, and community members will lead us to reject the poor relationship substitute provided by technologies like social media.

Conclusion: Is it Worth Reading?

If I haven’t already made it clear, I consider the book worth reading. It offers insights into the inner workings of the attention economy and gives plausible principles for resisting the baser and more damaging effects those digital technologies can have on us.

Living the virtuous life has always been a difficult, lifelong journey. Modern digital technologies seem engineered to make the virtuous life more difficult to pursue wholeheartedly. Therefore, we must understand what we are up against and work to navigate these challenges successfully. Digital Minimalism is a helpful book to read as one works to develop a healthy relationship with modern digital technologies.